a Flutter App Product

So, this is Orthogonality

I found the concept of Orthogonality in The Pragmatic Programmer

book. The authors encourage developers to create system that is

orthogonal whenever possible. Simply put, orthogonality, as I

understand it, means that if one part of the system is changed,

other parts are not affected and do not need to be adjusted. One way

to apply this is by ensuring that each component created has only

one purpose. Even though this lead to having more smaller

components, but it makes it easier for developers to work on each

component. Changes are not a nightmare to implement because they do

not disrupt other components. The system's units will be isolated

and independent.

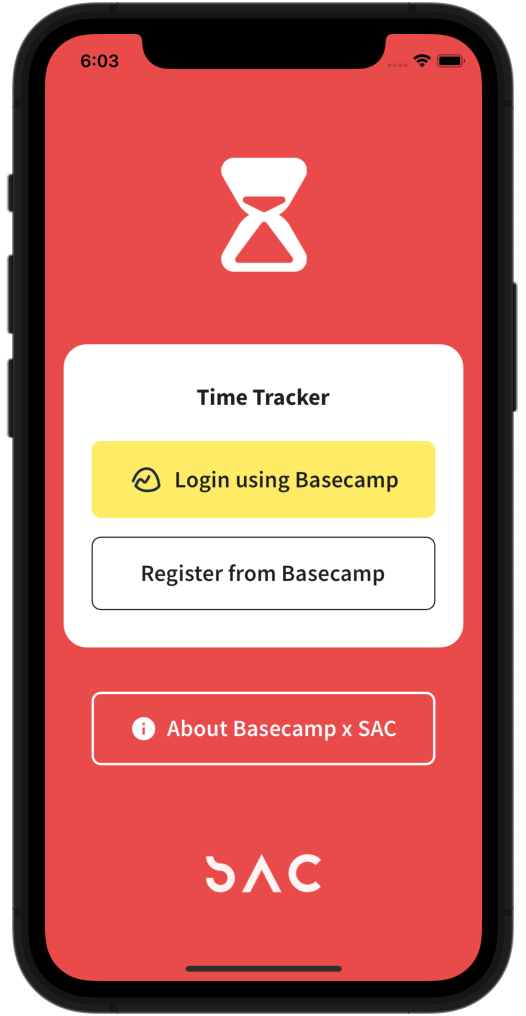

Unconsciously, my colleague and I applied this concept to an

internal office product. We named it Time Tracker. It is a mobile

application for recording employee task hours that synchronizes with

Basecamp (the project management platform used by our office). We

used Flutter to build this application. Flutter is a popular

framework built on the Dart programming language, allowing us to

create applications that can run on various platforms

(cross-platform). Both Flutter and Dart are developed by Google.

Flutter effectively abstracts the object-oriented programming

features of Dart.

At that time, Flutter was new to me. I immediately sought out a

comprehensive course to guide us in developing this application

whenever we got stuck. It turned out to take quite some time to

learn and experiment. Eventually, I told my colleague that we needed

to decide how the application would be developed to ensure it would

be maintainable in the future.

There were several architectural options, various state management

libraries to choose from, and considerations for how the API would

be consumed. In the end, I leaned towards the advice of an

experienced Flutter developer. Thank you

Andrea for

your Dart and Flutter courses, this is the recipe that I used:

-

Architecture:

Riverpod

-

State Management:

Riverpod

-

Important Dart Libraries: GoRouter, OAuth2, Sembast,

stop_watch_timer, http

- Design Pattern: Repository

The main goal was Separation of Concerns: separating the user

interface code from the business logic and separating the business

logic from the data flow.

Minimum Viable Product

This application was required

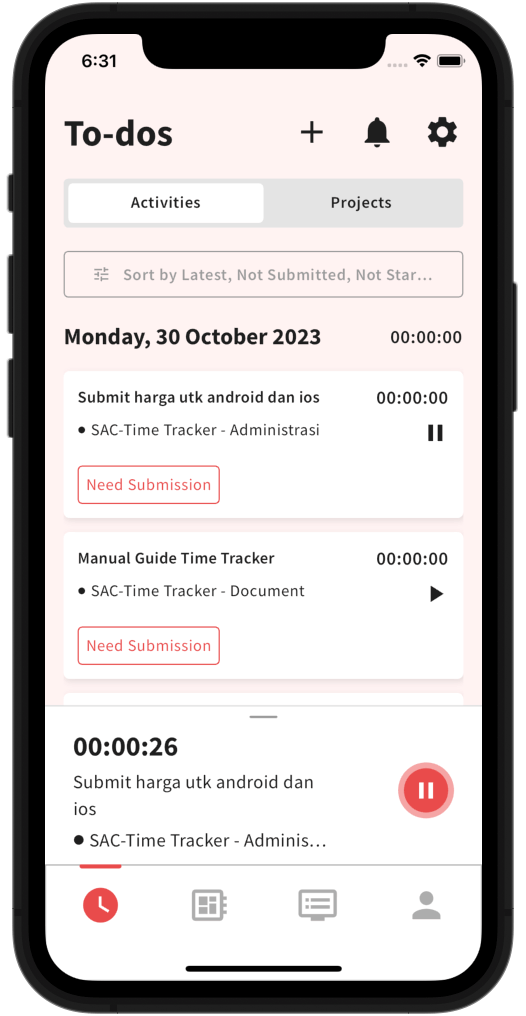

to record how long staff worked on a task. A

stopwatch feature with start, pause, stop, and save functionalities

was created to meet these expectations. The list of to-dos assigned

to an employee in Basecamp would be displayed in the application if

the employee logged in using their Basecamp account. Changes on

to-do metadata in the application, such as the duration of the

to-do, had to be persisted.

The flow is as follows: the user logs in with their Basecamp

account, their list of to-dos is displayed, the user starts a

stopwatch on a to-do, the stopwatch can be stopped and the elapsed

time for that to-do is saved, accumulating the duration from

previous ones.

Technical Implementation

This application is supported by a backend for accessing users'

Basecamp resources.

The Basecamp API uses OAuth2 to obtain user authorization for

accessing their related data. Therefore, the Time Tracker

application will direct users to the Basecamp consent page in a

browser for login and permission granting. The user will then be

redirected back to the application with an Access Token.

The Access Token provided by Basecamp was sent from the Frontend to

the Backend to be stored, so that this process didn't have to be

repeated until the token needed to be refreshed. At that stage, the

Backend had the authority to retrieve the user's To-do data. The

Frontend requested the To-do data from the Backend through an API

provided by the Backend. The Backend then supplied the requested

list of To-dos. Where did this To-do data come from? It was

periodically accessed from the Basecamp API by the Backend. Not all

To-dos came from Basecamp; our database also stored new To-dos

created by users through the Time Tracker application.

The To-do list provided by the Backend needed to be stored on the

user's device to keep the number of requests efficient and to

facilitate easy processing. This functionality was supported by

Sembast.

When a user ran the Stopwatch on a To-do, the application saved each

second locally. If the user wanted to switch To-dos or had finished

and wanted to save it, the Frontend sent the metadata of that To-do

to the Backend, ensuring it was persisted seamlessly.

The Hard Part

Not only user interface.

In my opinion, the challenging part of the MVP that I mentioned

earlier is the retrieval and management of user to-do lists. This

data originates from the backend's database and is also stored on

the user's device in the form of a NoSQL-style database file (.db)

that can be managed.

Data's Create, Read, Update, and Delete (CRUD) operations needed to

be implemented using Sembast as its interface. There was

synchronization between remote and local to-dos to ensure users

always had their to-dos in the latest state (without losing

progress). This synchronization had the potential to cause conflicts

if both data sources underwent changes, which was very tricky.

Valuable Lessons

Coding requires dedication and patience, to help us with that,

use the time to rest and think about the product.

Understands acceptance criteria and the product owner's expectations

for the application, then taking the time to describe how it works

will help direct the implementation to be on target. Draw the flow

if it is hard to imagine.

It is also crucial to maintain good and healthy communication with

the team, especially fellow developers, in my case the scope of the

product was large, because other features that we may not need. I

learned that collaboration is a key.